November 14, 2008 — Forty three years ago, Charles J. Byrne, a Bellcomm, Inc. engineer, became concerned about NASA's plans to archive the data to be sent from a series of Moon mapping precursor missions to the Apollo lunar landings.

The Lunar Orbiter telemetry, which just two years and five unmanned missions later would account for imagery of 99 percent of the Moon, was originally planned by the space agency to be recorded on photographic film only. The five orbiters themselves would carry the equipment to develop their film and then scan it for transmission back to Earth. Once there, it would then be reprinted in strip form to then be manually re-assembled and re-photographed for study.

Anyone who has used a copy machine to make a copy of a copy knows that resolution is lost in the process. The same was true for Lunar Orbiter, though for NASA, which needed quicker access to the data than computers of that day were able to provide, the resulting images would be what they needed to evaluate landing locations for Apollo.

Still, thought Byrne, there would be value to having a tape back-up, so he outlined his idea for a Lunar Orbiter DVR- like system in a July 1965 memo.

"It is concluded that the ability to fully optimize the later site survey missions on the basis of early Lunar Orbiter data depends on an immediate decision to provide tape recorders," wrote Byrne.

An AMPEX FR-900 recorder (left) is used at Goldstone. (NASA) |

NASA agreed and AMPEX FR-900 2-inch analog tape recorders were positioned at the Goldstone, California, Madrid, Spain and Castle Island (Woomera), Australia tracking stations to record all the images from the Lunar Orbiter spacecraft.

Byrne had referenced "later site survey missions" in his memo. What he didn't know -- what he couldn't know then -- was how much later those tapes would come back into use.

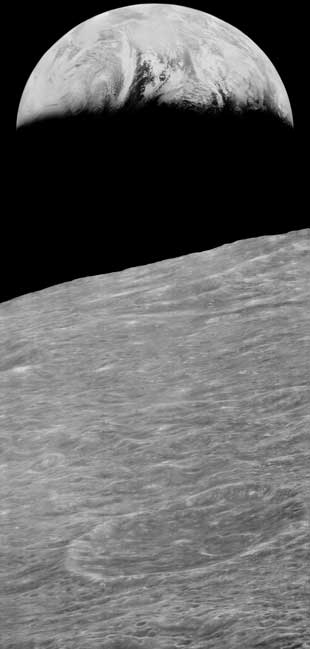

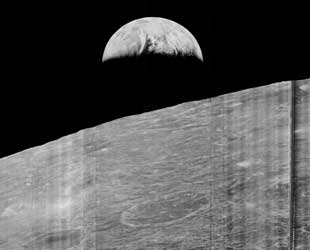

Earthrise and the sun sets on Lunar Orbiter

Though Lunar Orbiter was quickly overshadowed by the manned Apollo missions, they did accomplish a number of firsts. The spacecraft captured the first high resolution global map of the Moon, the first stereo imagery of the surface, and the first images of the Earth from the Moon.

The latter was particularly noteworthy as it amounted to the spacecraft's controllers turning Lunar Orbiter 1 away from the surface to take what was essentially an artistic shot. The black and white image was quick to capture the public's attention.

"There are two pictures that are iconic for somebody my age," said Keith Cowing, who was 11 at the time of Lunar Orbiter 1. "One is what LIFE magazine called the 'view of the century' which is the oblique shot of Copernicus crater taken by Lunar Orbiter 2 as I recall, and it was the picture of the century because up until then, I had never seen a sideways view of a mountain inside a crater on the Moon, nor had anybody else. That struck me that it was a world like Earth. It was almost like listening to what Galileo said about the fancible mountains of the Moon. This be the mountain!"

"And the other one of course, is earthrise, Earth rising above the surface of the Moon," continued Cowing in an interview with collectSPACE. "At the time, all the photos were either television or photographs that had been sent back and they were murky."

Lunar Orbiter's Earthrise, as originally released. (NASA/LPI) |

"Very shortly thereafter, we landed on the Moon and there were the ghostly images of people walking on the Moon."

That astronauts landed safely and explored the surface meant that the Lunar Orbiters had done their job. With the Apollo program coming to a close and without a pressing need for the Lunar Orbiter data, NASA put the tapes into storage, first in Maryland and then in the mid-1980s they were moved to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

That's where they came under the care of Nancy Evans, co-founder of the NASA Planetary Data System (PDS).

Evans, working with Mark Nelson of Caltech, began a project to obtain surplus FR-900 tape drives, refurbish them, and digitize the Lunar Orbiter analog data on the tapes. They were successful in so much that they were able to obtain the tape drives and get them running, but without funding the project folded.

By the early 1990s, Evans had retired from JPL, taking with her the government-surplused drives in the hope of finding private funding to continue the project she began.

A "cool little project"

The drives inside Nancy Evan's garage. (LOIRP/MoonViews.com) |

Unfortunately, the money would never materialize and Evans moved on to her second career as a veterinarian.

Nearly two decades would pass while the drives sat in her garage, collecting dust. Approaching a second retirement in 2007, Evans began searching for someone to take the drives and do something with them.

Dennis Wingo, author of "Moonrush: Improving Life on Earth with the Moon's Resources" and the president of the aerospace engineering company SkyCorp, Inc., was intrigued.

"In the spring of 2007, Dennis Wingo sent me a note saying, 'I found this posting on some internet board where someone says there are all these Lunar Orbiter tapes and someone apparently tried to get data off of them years ago'," described Cowing, who runs SpaceRef Interactive.

Cowing was intrigued but skeptical. "I said, 'Is this really worth doing?'" he admitted.

Wingo explained, recalled Cowing, the way in which the original Lunar Orbiter images were processed and how that resulted in a loss of resolution. Looking at the data now as it was released in 1966, "we discovered, among other things, these things had done imaging of the poles. The resolution was good, it could have been better, but again, all they had were photographs... or photographs of photographs."

The tapes being loaded for transport. (LOIRP/MoonViews.com) |

"We realized we could go get these tapes, we could go get these drives and if we can find a way to restore them, this would be a cool little thing to do," shared Cowing.

After verifying that the tapes were accessible, arranging storage space with NASA's Ames Research Center and insuring that the drives were more or less intact, Cowing invested his own money into renting a couple of trucks and he and Wingo set off through California to reunite the data with their recorders.

Moving into McMoon's

Cowing and Wingo needed a place to clean and restore the four refrigerator-size drives as well as sort through the 1,500 data reels.

"We really didn't need anything more than doors that locked and electricity," explained Cowing. "A workspace where if we messed it up with these drives and got it all dirty, no one would really care."

Ames had a number of buildings in their research park that could work, including a former military barber shop and a recently-closed McDonald's.

"At the time we thought we might have to use some type of noxious cleaning and [the McDonald's] had a ventilation fan, so we thought that would be perfect and there was a sink in the back with a big washing appartus. There were shelves and it was available, so we said, 'why not?'," said Cowing.

"We just jokingly call it McMoon's," he revealed. "People to this day come up thinking it's open. They walk in and stand there, and we've got all this electronic stuff laid out and they ask if they can get a hamburger. It is a routine if you work there that someone comes up once a day."

The drives inside McMoon's. (LOIRP/MoonViews.com) |

Of course, not all visitors are unwelcome.

"We were able to get some smart, local kids to help us with the electronics and processing," explained Cowing. "It wasn't so much that it was cheap, we felt we wanted to teach people at the same time."

"Today, you do electronics and at the sub-scale of the electronics components, you can't even them without a microscope. But with this stuff, you can actually see the resistors and capacitors and understand how these circuits work. So, having these kids touching stuff that was built when their parents were in grammar school, alongside people who had been there, the object lesson was how things were done and this stuff works. It's big and heavy and noisy, but it works."

And work it did. After a good cleaning (using the former McDonald's dish sink) and replacing parts by using two of the four drives as donors, the team after 99 days brought the 40 year old drive back to life.

"A lot of people thought this was impossible. Things that are 40 years old don't work," recalled Cowing. "I beg to differ. I have a KLH Model 14 [audio speaker] that I just got and it works just fine."

Re-discovering Earthrise

The next step was finding an example tape to run through the working drive. The tapes were still inside their storage boxes.

"This is sort of like archeology. These were probably last touched by people who are very dead and you can't call them up and ask, 'What did you mean by this?'", Cowing observed.

As they opened and unpacked each box, care was given to retain any of the labels that accompanied them, even though they did not always understand the nomenclature.

"The image we found was found because of the process I put in place," stated Cowing. "If there were any tapes that were not like the others, I had them put it in this one spot and it turned out that there were multiple tapes that were 'best of' tapes that, we think, were made a few years later [after the originals]."

The data tapes inside McMoon's. (LOIRP/MoonViews.com) |

Still, it took some experimentation to understand how the data was organized and what was on the tape.

"It was not unlike the scene from the movie 'Contact' where they think they have a video signal but they are not sure and they sort of monkey with the gear and they plug things in and they say, 'Hey look! That's a video signal'. As they play with it further they suddenly say, 'Oh look, maybe we rotate it that way, flip the contrast,' and they eventually find out they've got a video signal and they're sitting there and playing with it and 'Look, more data!' and that's how it happened," described Cowing.

"We went from, yes, we can confirm the heads play back the tapes and we do see a video signal to the signal conforms pretty much to what was in the documentation and then we now know how to do this and that."

The team, now working under the title of the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP), even found assistance by a chance visitor, Charles J. Byrnes.

Byrnes just happened to be attending a lunar conference at Ames when team members had just come across his 1965 memo. Once discovering he was there, they invited him to McMoon's.

Their first real clue however, as to which image they were processing came from an audio track that accompanied the data. The recording captured the voice of the tracking station operator, who mentioned seeing Earth.

Earthrise restored by the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project. The center portion containing Earth has undergone a second level of processing to remove the 'framelet' lines. (NASA/LOIRP) |

Processing the first few "framelets," Cowing was able to eventually match the slices to those from the 1966 photo of Earthrise.

The improvement in quality was immediately apparent. LOIRP's digitized image was twice the raw resolution of the scanned film archived by the U.S. Geological Study, and that was using a copy of a tape, not the original. The team had proven that their "cool little project" was worth doing.

NASA's use for the "time machines"

Beyond being 'cool' though, the LOIRP has the potential to contribute to NASA's return to the Moon.

NASA is preparing to launch its Lunar Reconnaisance Orbiter in 2009, a modern day Lunar Orbiter to map the Moon in search of new landing sites and lunar resources.

LOIRP's restoration of the Lunar Orbiter images to high resolution will provide the scientific community with a baseline to measure and understand changes that have occurred on the moon since the 1960s.

"This is a time machine," said Cowing. "It is reaching back into time and through history, bringing information forth. We want everyone to see it."

A "time machine" at work in McMoon's. (LOIRP/MoonViews.com) |

As the images are processed, they will be submitted to the Planetary Data System, which NASA's Space Science Mission Directorate in Washington sponsors in cooperation with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. The images also will be calibrated with standard mapping coordinates from the U.S. Geological Survey's Astrogeology Research Program in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Future images will be made publicly available when they are fully processed and calibrated.

"I feel personally that the interpretation of these images should be done by as broad a community as possible," shared Cowing.

First though, the drives need further work.

"We have pretty much used these drives to the extent that they can be used without a full overhaul," Cowing explained. "That requires pulling the bearings out, dipping them in liquid nitrogen and that's expensive," he added.

To that end, NASA's Exploration Systems Mission Directorate and Innovative Partnerships Program Office has provided initial funding for the project.

"It's a tremendous feeling to restore a 40-year-old image and know it can be useful to future explorers," said Gregory Schmidt, deputy director of the NASA Lunar Science Institute at Ames. "Now that we've demonstrated the capability to retrieve images, our goal is to complete the tape drives' restoration and move toward retrieving all of the images on the remaining tapes."