September 12, 2011 — A dead NASA satellite the size of school bus is falling back to Earth and where it will drop no one knows, at least not yet. The space agency is clear however, where the satellite's debris will not end up: eBay.

Launched in 1991 on board space shuttle Discovery, the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) completed its mission studying the chemicals in Earth's atmosphere in 2005 and since then has been gradually falling out of orbit. U.S. Strategic Command at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., which tracks man-made objects circling the planet, expects UARS to plunge back to Earth during the last week of September.

Daily changes in the atmosphere make predicting exactly where UARS will fall difficult, according to Maj. Michael Duncan, the deputy chief for space situational awareness at U.S. Space Command.

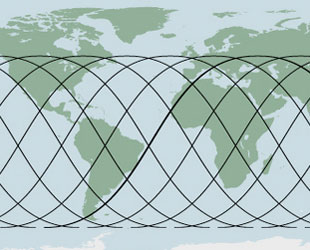

"We do know with 99.9 percent accuracy that it'll reenter the atmosphere somewhere between 57 degrees north and 57 degrees south, which means it will be anywhere from northern Canada to southern South America and that is truly the best estimation we can give you at this point of time," Duncan told reporters on Friday (Sept. 9). "It takes until it gets much closer to the actual reentry time before we can give any sort of prediction better than that."

As of Sept. 12, UARS was orbiting 145 by 165 miles (235 by 265 km) at a 57 degree inclination. (Graphic: Space.com Infographic) |

NASA's orbital debris program analyzed UARS's design in 2002 with the purpose of determining what, if any parts of the satellite would survive the fiery reentry and make it to the ground.

"We believe there will be 26 different components that will hit the surface of the Earth somewhere with a total mass of a little over 500 kilograms [1,100 lbs]," NASA's orbital debris program chief scientist Nick Johnson said. "The largest piece that we think is going to come back is part of the structure of UARS and it is going to have a mass of just in excess of 150 kilograms, so a little more than 300 pounds."

There is a 1-in-3,200 chance that one of those pieces will land on someone somewhere in the world. Those odds are "very, very low" Johnson said, pointing out that in the 54 year history of the space age, "there have been no reports of anybody in the world being injured or severely impacted by any reentering debris."

But pieces do make it to the ground.

"Typically, we find one piece a year from these reentries," Johnson said, describing moderate-size objects. UARS is significantly larger.

Look, but don't touch

Most of the world's population lives within the area where UARS may fall. Should any of them be under the satellite when it comes back to Earth, they may be in for quite the sky show.

NASA's UARS measures 35 feet long and 15 feet wide and has a dry weight of 5.7 tons. (Graphic: Space.com Infographic) |

"If they are fortunately positioned, this should be quite a nice show," Johnson said. "It's a relatively large vehicle. It would be visible in the daylight."

"Odds are though, it will happen over an ocean, unlikely to be seen unless it is by an airliner — and we've had reports like that before. Since we don't know where it is going to come in, we can't raise people's expectations and tell them to go out and look in the backyard," he said.

Even so, NASA is already warning the public through its website that should they find something they think may be a piece of UARS, "do not touch it."

"We always tell people not to go pick things up because that is always safe," Johnson said. "You are much more likely to get cut by some sharp edge on a piece — there are no hazardous materials [and] there are no radiological materials [aboard]. So it is always best to leave it where it is, notify your local authorities and they will contact us and we will work whatever needs to be worked."

Depending on the nature of the debris — whether a large tank or a small nondescript component — that work is more likely to be about safely disposing of the debris than recovering it for scientific study.

"Obviously when a tank is found, or another component is found around the world, we do have an interest in it. We go try to verify the identity but most of the time, it is a very large tank, it is made out titanium or stainless steel, and we know very well that those are going survive. They may not ever be found, but we know they are going to survive. So there really is not a whole lot we can learn from those tanks," Johnson said.

"The smaller components that also might survive are rarely recognized for what they are. You know, if you are out walking on a pasture or in the woods and you see this hunk of metal out there, you're first assumption is not that it is some part of a satellite that fell to Earth. But we do get calls and e-mails from people around the country on a regular basis about things they think they found that may have come from a reentering satellite. And almost without exception, they're found to have some other source," he said.

Finders not (necessarily) keepers

Science aside, NASA's interest in recovering the debris is not just about protecting the public but also enforcing the law, Johnson said.

"Because this is a U.S. government satellite, any object that does reach the surface of the Earth, should it be found, is still the property of the United States," he said.

"You do not have the luxury of trying to sell it on eBay."

But where it falls does make a difference. If it lands within the boundaries of the United States, then "U.S. laws and regulations apply," Johnson said.

Should UARS drop debris outside the U.S. however, then the United Nations (UN) becomes involved.

"If it lands outside the United States, then it is covered by a UN convention. What that convention says is that the United States can request that that object be returned to it. And If the country where it fell is a signatory to that convention, then they are obligated to return it, although the United States has to pay for the transportation cost," Johnson said.

The convention, the "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies" or more simply, the "Outer Space Treaty," entered into force in October 1967. According to the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs, 100 nations are party to the treaty.

"The United States can and has in the past requested the return of objects. But it's our option. It is not a requirement they be returned," Johnson said.

The U.S., for example, did not request the return of the debris from Skylab when it fell over the Australian outback in 1979. Pieces of the fallen space station were later sold as souvenirs and commercial collectibles.

But not all spacecraft debris has been released to become mementos, or for that matter, hot tubs.

"A component from a European launch vehicle washed ashore near Corpus Christi [Texas] and someone in the area found it on the beach. It looked like a nose cone from one of the booster rockets for the Ariane [launch vehicle]," Johnson said.

"He actually wanted to keep it and put it in his backyard and make a hot tub out of it. We however, convinced him with help from our colleagues at the Department of Justice that that was not an option. We did retrieve that object," Johnson said.

"We would do the same thing for any objects recovered in the United States from UARS."