advertisements advertisements

|

|

NASA, university researchers release 19,000 hours of Apollo 11 audio

July 25, 2018 — NASA has a new playlist perfect for counting down to next year's 50th anniversary of the first moon landing.

Well, it is almost perfect. If you were to hit play on the agency's Apollo 11 audio archive today and let it go, non-stop, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it would not only still be playing on July 20, 2019 — half a century after Neil Armstrong's "one small step" — but would continue playing for another year, straight through the historic mission's 51st anniversary as well.

The product of a partnership between NASA and the University of Texas at Dallas (UT Dallas), the audio archive contains the complete record of the hundreds of separate conversations that took place between flight controllers and other ground teams supporting the Apollo 11 mission. The 19,000 hours of communication tracks, called "loops," span the entire journey from Earth to the moon and back.

"We're approaching the 50th anniversary of Apollo, and I'm really pleased that this resource is becoming available," said Mark Geyer, director of NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, home to Mission Control. "These tapes offer a unique glimpse into what it takes to make history."

The key Apollo 11 comm loop, the air-to-ground exchanges between astronauts Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins with Mission Control, was released to the public as the mission played out in real time 50 years ago. But the other loops, the myriad of "backroom" discussions where engineers and scientists discussed the mission's fine details, have been locked away on tapes, preserved in climate-controlled vaults.

Those loops have never been easily available to the public due to technical and logistical hurdles.

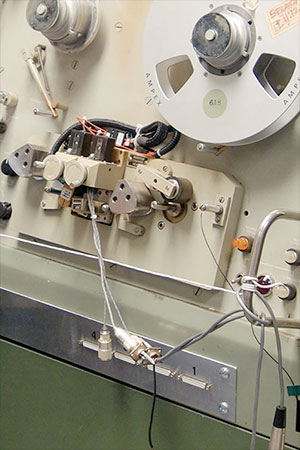

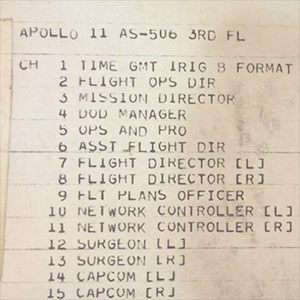

To begin, the only remaining functional machine capable of playing back the 170 or so tapes is in NASA's possession. To convert the audio to digital for wider distribution required that the SoundScriber's deck be modified to handle the tapes' 30 separate audio channels at the same time. Further, because the tapes also included the silence between conversations, a system was needed to recognize the starts and stops, as well as "hot spots" such as laughter, to output transcripts of the conversations.

Fortunately for the space agency, the scientists at the Center for Robust Speech Systems (CRSS) at UT Dallas' Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science were up for the challenge.

Funded by a National Science Foundation grant, the team at CRSS developed the speech-processing techniques to reconstruct and transform the massive audio archive into "Explore Apollo," a website to provide public access to the recordings. The project, in collaboration with the University of Maryland, included audio from the complete Apollo 11 mission and most of the Apollo 13, Apollo 1 and Gemini 8 missions.

"The effort is a way to contribute to recognizing the countless scientists, engineers and specialists who worked behind the scenes of the Apollo program to make this a success," said John H.L. Hansen, principal investigator for the effort. "These are truly the 'heroes behind the heroes' of Apollo 11!"

The conversations revealed by the archive provide insight into the "humans in the loop" that made Apollo possible. For example, there is one spot in the tapes where two NASA flight controllers are working with Aldrin because the sensor measuring his breathing was not operating properly.

In the excerpt, the men in Mission Control explore a number of possible reasons for the problem, ask questions, and maybe 10 to 15 minutes go by. Finally Aldrin, exasperated by the troubleshooting, informs the ground, "Well, if I stop breathing, I'll be sure to let you know!"

In another example, a flight controller responsible for putting video on the large screens on the front wall of Mission Control offers a channel where the flight controllers could view the black and white footage at their consoles. Flight Director Gene Kranz subsequently informs him that the consoles are only to be used for looking at data.

The project, which included the work of a dozen people from Johnson's external relations office, began in late 2013 and was completed earlier this year. Over the course of those five years, the UT Dallas and NASA personnel had to take care not to damage the historic audio tapes while also working around NASA's real-time audio projects, including supporting International Space Station operations.

"It was a such a daunting task, so many challenges, so many problems to solve," said Greg Wiseman, the project's lead audio engineer in Johnson Space Center's communications and public affairs office. It was made possible by the many people "who cared about the preservation of history and finding a way to release this to the public."

And the work continues. The 19,000 hours that comprise the Apollo 11 archive represents only 25 percent of the record for all of Project Apollo. The remainder cover the early Apollo test flights that circled Earth, the Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 missions that orbited the moon and the five later missions that landed on the moon after Apollo 11.

The project is also aimed at developing new techniques for processing "noisy" audio channels, to find ways to identify when conversations begin in the midst of long sections of silence and devising methods to identity and track speakers by topics, keywords, the speaker's state of mind and noise from their surrounding environments.

"This project brings together the massive multimedia archives of one of the best documented events in all of human history, the Apollo lunar missions, to create [an] experiential interaction with historical materials," said Hansen. "[The archive is] so rich that [it] will in some ways exceed what could have been experienced by any participant at the time."

Access NASA's Apollo 11 Mission Operations Control Room audio archive here. |

|

NASA's SoundScriber needed to be modified with a new 30-track tape playback head in order to digitize the Apollo 11 backroom loop audio archive. (UT Dallas)

An example of the computer print-out of an audio track sheet of a 30-channel Apollo analog tape showing channel information of all tracks. (NASA)

Mission Control during the historic Apollo 11 moonwalk. (NASA) |

|

© collectSPACE. All rights reserved.

|

|

|

|